Chapter 3: Modernism - Racism - Extermination II

- Heterophobia (resentment of the different) seems to be a focused manifestation of a still wider phenomenon of anxiety aroused by the feeling that one has no control over the situation, and that thus one can neither influence its development, nor foresee the consequences of one's action. Heterophobia may appear as either a realistic or an irrealistic objectification of such anxiety--but it is likely that the anxiety in question always seeks an object on which to anchor, and that consequently heterophobia is a fairly common phenomenon at all times and more common still in an age of modernity, when occasions for the "no control" experience become more frequent, and their interpretation in terms of the obtrusive interference by an alien human group becomes more plausible.

- Contestant enmity is a more specific antagonism generated by the human practices of identity-seeking and boundary-drawing.

- Bauman argues that racism differs from both heterophobia and contestant enmity. The difference lies neither in the intensity of sentiments nor in the type of argument used to rationalize it. Racism stands apart by a practice of which it is a part and which it rationalizes: a practice that combines strategies of architecture and gardening with that of medicine--in the service of the construction of an artificial social order, through cutting out the elements of the present reality that neither fit the visualized perfect reality, nor can be changed so that they do.

- In a world notable for the continuous rolling back of the limits to scientific, technological and cultural manipulation, racism proclaims that certain blemishes of a certain category of people cannot be removed or rectified--that they remain beyond the boundaries of reforming practices, and will do so for ever.

- According to George L. Mosse [Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism], "it is impossible to separate the inquiries of the Enlightenment philosophies into nature from their examination of morality and human character ... [From] the outset... natural science and the moral and aesthetic ideals of the ancient joined hands." In the form in which it was moulded by the Enlightenment, scientific activity was marked by an "attempt to determine man's exact place in nature through observation, measurements, and comparisons between groups of men and animals" and "belief in the unity of body and mind". The latter "was supposed to express itself in a tangible, physical way, which could be measured and observed". What was left to racism was merely to postulate a systematic, and genetically reproduced distribution of such material attributes of human organism as bore responsibility for characterological, moral, aesthetic or political traits. Even this job, however, had already been done for them by respectable and justly respected pioneers of science, seldom if ever listed among the luminaries of racism.

- Only with the modern reincarnation of Jew-hatred have the Jews been charged with an ineradicable vice, with an immanent flaw which cannot be separated from its carriers.

- It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to arrive at the idea of extermination of a whole people without race imagery; that is, without a vision of endemic and fatal defect which is in principle incurable and, in addition, is capable of self-propagation unless checked. It is also difficult, and probably impossible, to arrive at such an idea without the entrenched practice of medicine (both of medicine proper, aimed at the individual human body, and of its numerous allegorical applications), with its model of health and normality, strategy of separation and technique of surgery. It is particularly difficult, and well-nigh impossible, to conceive of such an idea separately from the engineering approach to society, the belief in artificiality of social order, institution of expertise and the practice of scientific management of human setting and interaction. For these reasons, the exterminatory version of anti-Semitism ought to be seen as a thoroughly modern phenomenon; that is, something which could occur only in an advanced state of modernity.

- Racism, even when coupled with the technological predisposition of the modern mind, would hardly suffice to accomplish the feat of the Holocaust. To do that, it would have had to be capable of securing the passage from theory to practice--and this would probably mean energizing, by sheer mobilizing power of ideas, enough human agents to cope with the scale of the task, and sustaining their dedication to the job for as long as the task would require. By ideological training, propaganda or brainwashing, racism would have to imbue masses of non-Jews with the hatred and repugnance of Jews so intense as to trigger a violent action against the Jews whenever and wherever they are met. According to the widely shared opinion of the historians, this did not happen. In spite of the enormous resources devoted by the Nazi regime to racist propaganda, the concentrated effort of Nazi education, and the real threat of terror against resistance to racist practices, the popular acceptance of the racist programme (and particularly of its ultimate logical consequences) stopped well short of the level an emotion-led extermination would require. This fact demonstrates the absence of continuity or natural progression between heterophobia or contestant enmity and racism.

- Sabini and Silver ["Destroying the Innocent with a Clear Conscience: A Sociopsychology of the Holocaust", in Survivors, Victims, and the Perpetrators] shows that the most successful--widespread and materially effective--episode of mass anti-Jewish violence in Germany, the infamous Kristallnacht, was a pogrom, an instrument of terror ... typical of the long-standing tradition of European anti-Semitism not the new Nazi order, not the systematic extermination of European Jewry.

- Mob violence is a primitive, ineffective technique of extermination. It is an effective method of terrorizing a population, keeping people in their place, perhaps even of forcing some to abandon their religious or political convictions, but these were never Hitler's aims with regard to the Jews: he meant to destroy them. There was not enough "mob" to be violent; the sight of murder and destruction put off as many as it inspired, while the overwhelming majority preferred to close their eyes and plug their ears, but first of all to gag their mouths. Mass destruction was accompanied not by the uproar of emotions, but the dead silence of unconcern. It was not public rejoicing, but public indifference which "became a reinforcing strand in the noose inexorably tightening around hundreds of thousands of necks." Not that indifference itself was indifferent; it surely was not, as far as the success of the Final Solution was concerned. It was the paralysis of that public which failed to turn into a mob, a paralysis achieved by the fascination and fear emanating from the display of power, which permitted the deadly logic of problem-solving to take its course unhampered.

- The true role of the sophisticated, theoretical forms of racism/antisemitism lay not so much in its capacity to foment the antagonist practices of the masses, as in its unique link with the social-engineering designs and ambitions of the modern state (or, more precisely, the extreme and radical variants of such ambitions). One can assume that when situations calling for a direct take-over of social management by the state happen in some not too distant future, the well-entrenched and well-tested racist perspective may again come handy.

1

1

It’s time to finish up this week with some great news. As always we present you several new functions on

It’s time to finish up this week with some great news. As always we present you several new functions on

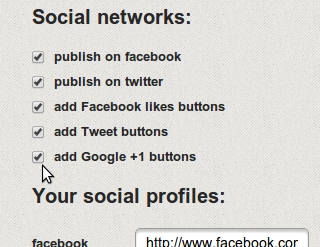

Just connect your Fb account in

Just connect your Fb account in  Your writing will also get additional social component: share buttons that can be added to your posts and reviews on your blog. Then your guests and blog visitors can easily spread the word and share your writing. Share buttons are optional, you can decide whether you want to add them or not. To switch them on go to your

Your writing will also get additional social component: share buttons that can be added to your posts and reviews on your blog. Then your guests and blog visitors can easily spread the word and share your writing. Share buttons are optional, you can decide whether you want to add them or not. To switch them on go to your  1

1